Paddling Kadavu Island

As our sea-kayaks slide up the rough-grained yellow sand, a muscular figure crunches down the beach towards us.

He looks about 35, is around 6 ft, and I guess he’s a lean 85 kilos. As he gets closer I see he hasn’t yet sacrificed his front teeth to the great Rugby God, a minor miracle in this mouth-guard free nation. I will notice later that he doesn’t wear a wrist-watch. It is only the visitors to this place who feel the need to know the time.

“My name is Joe. I am the Warrior of the Village ”

Now that’s an impressive introduction. Maybe Joe uses this line to impress the few travelers who come his way. I study his face for the tell-tale hint that he is hamming it up for the Aussie tourists. There is not the flicker of an eyelid. Joe is serious!

“My father and grandfather were the Warriors of the Village and their fathers before them.”

A single bead of sweat makes its way slowly down my spine, as I give Joe a surreptitious once-over for a concealed war club. He continues, deadpan:

“The Warrior of the Village guards the Headman and protects the visitors. You and your belongings will be safe tonight. I will stay awake until early morning in case bad people come from another village.”

Joe smiles and extends his hand.

“Joe, it’s great to meet you. I’ve never felt safer in my life.”

Such was our welcome to the village of Naqara on Ono Island. It’s one of 300 Fijian islands, but a world away from the swimming pools and uniformed waiters of the tourist resorts.

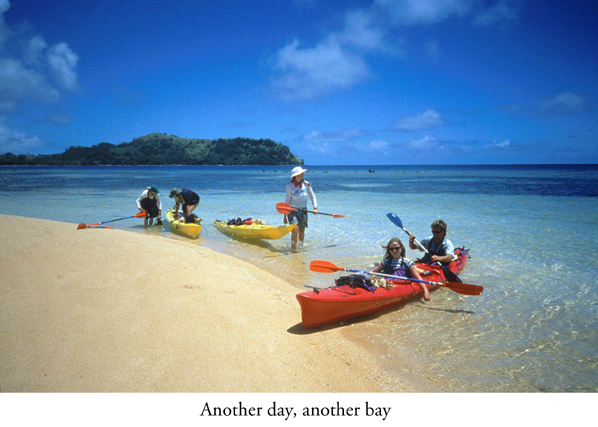

We are four paddlers, in two double sea-kayaks. Debbie and me in one, and a young couple from Melbourne, Martin and Tania, in another. Our leader is Tony Norris of Tamarillo Tropical Expeditions from Wellington, New Zealand.

We have 3 Fijians with us: an experienced old salt called George, our boatman Joeli, and Joseva, a young trainee.

Paddling along the coast of Kadavu Island we have been protected from the Pacific swells by the Great Astrolabe Reef which surrounds both Kadavu and Ono. We have stayed each night at a remote fishing or diving resort, pausing during the day at pristine beaches and reefs for swimming and snorkeling.

This morning we paddled across the channel separating the two islands, and then around to Ono’s north shore to Naqara. This will be our first contact with what remains of the traditional Fijian lifestyle.

As we paddled into the sheltered bay a couple of young boys played hide and seek with us as they ran through the coconut groves waving and grinning. A solitary single-masted yacht rode at anchor reflecting into the ripple-free water. The couple on board had arrived a month ago for a two day stopover. It proves to be that kind of place.

As we unload our gear the smiling kids compete to carry our bits and pieces into the village. A small boy misses out so I hand him my water bottle. He races after his bigger mates holding the plastic bottle aloft with all the pride of an Olympic torchbearer.

As we enter the village we remove our hats. By custom it is only the chief who may wear a hat in the village. The girls cover up to ensure they do not give offence.

Joe points out the sights. Even when everyone is at home the village has less than 100 people. The 20 or so houses are built from scrap timber with rusted galvanized iron roofing. Paint is non-existent. Most have an outdoor kitchen with a fuel stove. If our homes were blown over by a hurricane every 10 years or so, maybe we would have the same attitude.

There are 2 churches; one a Methodist and the other Pentecostal. These are a conservative and religious people.

Between the village and the jungle there are extensive gardens and an array of tropical fruit trees. Dogs and hens wander unhindered. Under a banyan tree I see a muddy sty with a few pigs.

Joe shows us to 3 spacious bures. Each is constructed over a frame of natural timber, tied together with jungle vines, with uprights anchored into the ground. The roof and walls are thatched with palm leaves. The inside walls are mats of woven palm fronds. There is an outside shelter with a cold shower and a miraculous flushing toilet. Everything is spotless.

One of the churches is strongly built of concrete bricks and a sturdy-looking steel roof . A generator provides light, while the rest of the village makes do with kerosene lamps. The building serves as a community centre, primary school (3 teachers live in the village) and hurricane shelter. It is to here that Joe directs us for the evening meal.

The women of the village have laid out a feast on the only table. There is an abundance of tropical fruits including pawpaw, pineapple, mango and grapefruit . Freshly-caught reef fish are set out on banana leaves with dalo, cassava and pumpkin from the village gardens. We eat cross-legged on the woven mats, washing our meal down with freshly-squeezed fruit juice.

I notice there is a “missing generation “in the village. I soon learn the teenagers stay with extended family in Suva or Nadi when attending high school and many remain there to take jobs in the tourist industry.

A few of the young men start strumming their guitars and the kava bowl is filled. Being the oldest (easily discernable) of our group I am honoured with the first drink. As custom dictates, I clap before accepting the bowl, and don’t remove it from my mouth before draining the murky brown liquid, then clap three times before returning the bowl.

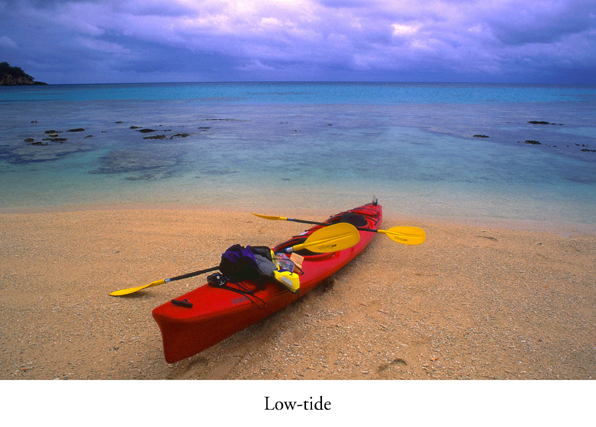

Kava looks and tastes like what it is, the sun-dried roots of a tropical plant, crushed into a powder, and hand-squeezed in water. My dentist could learn from these guys: after several bowls, my tongue and mouth have gone totally numb and could withstand root canal treatment. I gain relief when I learn I may ask for a “low tide” without giving offence to our generous hosts.

As the drinking and singing continues, I chat with as many of the locals as I can. The older men are universally quiet and dignified and share a few words. The women are shy.

I respectfully ask if I may take photos. I undertake to get prints back to the village. After this trip I will mail them to our guide Tony Norris who will hand them around on his next visit. Using the digital screen, I can give each person a preview. It’s always a great hit in places where cameras are rare.

It’s not much after 9 o’clock when the strenuous paddling, hot tropical sun and the kava take their toll. We say our goodnights and head for our bures. Joe materializes out of the darkness and escorts us. “You can leave your boots outside to dry. I will take care of them ”

Sleep comes quickly.

I wake up after my usual 7 hours sleep, but it’s still dark, so I roll over. It’s light the next time my eyes open, but I don’t hear much happening. No cars, no buses, no news on the hour. It’s quiet. Debbie is still in dream-land, so I pull on a pair of shorts and sit in the doorway watching the village slowly come to life.

A few people are walking about and we exchange a “bula” and a wave. I wonder if we appointment-driven, long-commuting city-dwellers are permanently sleep-deprived. Maybe that causes some of our stress.

I take a stroll, and under a big shady tree, I see a fit-looking man about my age working on a small outrigger sailing canoe. His grandchildren are playing nearby. I ask a couple of questions and he tells me a story from when he was a young boy.

The man’s father, mother, he and his siblings were sailing from Viti Levu (the big island) back to Ono. A sudden tropical storm blew in, the seas came up, and the large wooden skid on the outrigger broke free and was lost.

Without the balance provided by the skid, the outrigger tipped over and they all went into the sea. His father used his strength to right the craft, and remained in the water to provide the counter-balance to keep the boat upright. His mother handled the sail and the kids paddled and bailed. It took several hours for them to return to Viti Levu and safety.

Joeli our boatman later confirmed the older man’s story. They tell me he still dives on the reef each day for fish to feed his grandkids. These people are born to the sea.

Breakfast in the community centre is a repeat of last night’s feast with the addition of hard-boiled eggs from the half-wild hens we have seen flapping and scratching around the ground.

Debbie was raised in Fiji so Tony asks her to accept the honour of thanking our hosts. Debbie does it in style, including a smattering of Fijian remembered from her childhood. As she refers to each group; the guitarists, the women, the kava-makers and the children, she is acknowledged by deep throated ‘vinaka’s’ (thank you’s).

When it’s finally time to leave the whole group – men, women and children, break into a beautiful rendition of “Isa Lei”, Fiji’s haunting song of farewell. It’s a lip-trembler at any time, and it does a good job on this occasion.

We walk down through the village to the kayaks and load our gear. The Warrior of the Village leaves us with a few last words: “I have brothers and sisters in Suva, and I have worked there myself. But I prefer life in the village. I catch my own fish, grow my own vegetables and I have my own house. I can live on $20 a month.”

‘Joe, thank you and good luck. In a lot of ways, I envy you. Moce, goodbye.”